On February 6th of this year, the Leon Gallery, located in Makati City, held an auction of 73 works of art by Fernando Zóbel de Ayala (1924-84). The article that follows, which was written for the auction catalog by John Seed, describes the friendship between Zóbel and Jim and Reed Pfeufer, from whose estate the works had come.

“If I’m not mistaken I think I was six when I first met him (Fernando Zóbel). And through the eyes of a 6 year old it was all magic.” – Eric Pfeufer

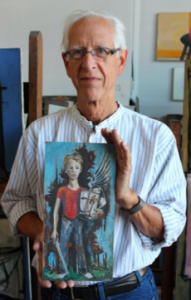

For years, Eric Pfeufer, 72, has carried fond memories of Fernando Zóbel de Ayala (1924-1984), the Philippine/Spanish modern artist who befriended his family while a student at Harvard after World War II. Eric’s parents, Jim and Reed, served as mentors to the young artist, supporting his interest in art and providing him a home away from home.

The Pfeufer’s home, in Cambridge, not far from Harvard Square, was modest and decidedly Bohemian. The walls were filled with art, and Reed had painted on many of the home’s surfaces: a naked Adam and Eve appeared on the doors of the kitchen cabinet, with a snake peeking from between their legs. Zóbel was one of a number of young Harvard men — aesthetes, architects and intellectuals — who hung out at the Pfeufer home, where the cultured conversations often went late into the night.

After his graduation in 1949 Zobel returned to Boston periodically — to serve as a curator at the Houghton Library in 1951-2 and again to exhibit his work in 1954 — and during these visits he painted and drew both the Pfeufer parents and all three of their children.

“I was just taken in by the, this miraculous person who just came and arrived and then became so close with the family. It was just a completely comfortable friendship.”

For Fernando Zóbel, who had grown up in a mansion in Manila, surrounded by the members of a wealthy, aristocratic family, the Pfeufers must have provided a very different kind of ambience: when asked for his political affiliation on a Harvard form Zóbel had entered “Monarchist.” The Pfeufers were down to earth, politically liberal, devoted to art rather than business, and far from affluent.

After marrying in the mid 1930’s Jim and Reed Pfeufer first lived in Plympton, Massachusetts. Both were used to frugality: Jim had been unemployed during the depression until he found a job supervising artists for the WPA. In 1941 the couple moved with their children Martha and Joachim to Cambridge where Jim took a position teaching shop classes at the Shady Hill School. Eric, the couple’s third child, arrived in the spring of 1942.

Jim Pfeufer, the grandson of members of the German Freethinkers movement who had settled in Texas in around 1848, grew up in Harlem and studied electrical engineering at the City College of New York. Jim was a jack-of all-trades, a clarinetist and a devoted father. Although he was not making art when Fernando first appeared, Jim later became a printmaker who taught at the Rhode Island School of Design.

Reed Champion was a native of Newton, Massachusetts, the daughter of a Yale graduate, Walter Julius Champion, and a musician mother, Alice Viola Champion. Raised in the Quaker tradition, Reed was taught to respect others and also that women were equal with men. Her mother, who was intensely creative, attended the New England Conservatory while Reed was a girl, also painted, had an interest in arts and crafts, and founded a theatre.

Reed’s father, a lover of the classics, read her Plato before she was five years old, and by the age of twelve she was steeped in myths, fairy tales, and the writings of Balzac and Hawthorne. Reed first displayed an interest in art while attending the Moses Brown School in Providence, Rhode Island. She later attended the Museum of Fine Arts School in Boston, where she studied with Wallace Harrison, an École des Beaux-Arts graduate and the architect of Rockefeller Center.

Reed was active as an artist during the war years, showing in group exhibitions at Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art in 1943, and again in 1944 when her work was shown alongside that of Jack Levine and Hyman Bloom, two of Boston’s leading modern painters. Like other artist’s connected with “The Boston Style” both before and after the war, Reed was representational painter whose art leaned towards Expressionism.

For Fernando Zóbel, who started his career painting representationally, Reed’s paintings were touchstones and also a point of departure. In a 1958 letter addressed to “Dearest Reed”, Zóbel acknowledged the importance of her work:

“Your pictures seem so natural and alive to me that I find them hard to view as something separate. They are very much a part of me I know, and my own pictures, though they seem perhaps so very different, in some obscure way lean on yours, in my mind, for support and reflection.”

Throughout the 1960s, 70s and 80s, the Pfeufers kept in touch with Zóbel as his reputation and stature grew. Eric and his brother Joachim both spent periods of a month or more staying with Zóbel in Spain, and Eric was there when the Museum of Spanish Abstract Art — which Zóbel founded — was in its early stages. Jim and Reed came to Cuenca in 1974. Eric remembers one last visit with Zóbel at the Harvard club just a few years before his sudden death at the age of 60 in 1984. “When I was with Fernando,” Eric recalls, “it was just the joy of knowing him. He was always generous and focused on his painting.”

Since his parent’s deaths — Reed passed away in 1997, followed by Jim in 2001 — Eric has been tending their estate, which includes five Zóbel oil paintings. One of them, “Garden Window” (1953) shows Joachim’s trumpet perched in front of the window of the Pfeufer’s home. Besides the portrait of Eric there is a slender, four- foot high portrait of Joachim, and also a dark, comic portrait of Jim holding his clarinet.

Earlier this year, Eric was visited by two Zóbel experts, Rafael Perez-Madero and Sheldon Geringer, both of whom were interested in seeing his Zóbel paintings. Stimulated by their visits Eric went through the flat files his parents had left in their home on Cape Cod and was stunned by what he found. Not only were there original Zóbel works on paper, prints and notebooks, but also a large abstract “Saeta” on paper. It was an unexpected treasure trove.

“It’s a joy to see Fernando’s work re-emerge.” Eric notes, “and a shock to me because my parents had flat files not only of Fernando’s work but of other people’s. I wasn’t every aware that these things were there.” Some or all of the prints were made in Jim Pfeufer’s studio in the basement of the Cape Cod house, where he assisted Zóbel with his printmaking. “Fernando had the benefit I would say of my father’s experience,” Eric points out. “My father had started as a painter himself and as time went by he became more engaged in etchings a various kinds of mediums.”

The treasured works that were part of Jim and Reed Pfeufer’s estate are a testament to an enduring friendship that revolved around art and love. In an undated letter written from Cuenca, Spain, Fernando Zóbel made a point of reminded the Pfeufers of the crucial role they had played in his life: “Much love to you. I think of you very often and I like you very much indeed. You have given color to my whole life.”